Keeping mental health alive when tracking progress on climate adaptation

Hear from Alessandro Massazza, our Policy & Advocacy advisor as he reflects on his time in Bonn, Germany, for the June UN Climate Meetings (SB62).

2nd July 2025.

Presentation by the health expert working group during a mandated event on the Global Goal on Adaptation at SB62 in Bonn | Photograph by Alessandro Massazza, United for Global Mental Health

Presentation by the health expert working group during a mandated event on the Global Goal on Adaptation at SB62 in Bonn | Photograph by Alessandro Massazza, United for Global Mental Health

In the last two weeks, countries from all over the world met in Bonn, Germany as part of the June UN Climate Meetings (SB62).

Across the various items that were discussed in Bonn (see health-specific summary from the Global Climate and Health Alliance here, and a general summary of the negotiations here), one of the items where mental health featured was in the context of discussions on the Global Goal on Adaptation (or GGA).

What is the Global Goal on Adaptation?

While it’s essential that countries transition away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly, and equitable manner to stop climate change, it’s also important that communities around the world are protected from the impacts of climate change that are already happening. This is known as adaptation.

The Global Goal on Adaptation was established in the context of the Paris Agreement as a global goal of enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience, and reducing vulnerability to climate change.

The GGA is supposed to outline a clear framework and targets that countries can use to monitor their progress on adaptation. For more detailed information about the GGA see here.

Why is mental health relevant to adaptation discussions?

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicates, with high confidence, that climate change has already been negatively impacting mental health globally, and these impacts are expected to worsen as climate change deepens.

Climate change is making extreme weather events more frequent and intense, exposing people to potentially traumatic events such as loss of loved ones and serious injuries, therefore increasing the risk of people developing new mental health problems such as depression, substance misuse, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Extreme weather events can also negatively impact mental health indirectly by worsening the social determinants of mental health such as economic inequality and gender-based violence. Furthermore, people with pre-existing mental health conditions can be more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. For example, people living with certain mental health conditions are at higher risk of dying during heatwaves.

Adaptation is therefore fundamental in order to ensure that the mental health of people and communities is protected from the impacts of climate change.

How does mental health currently feature in the Global Goal on Adaptation?

At the end of 2023, at COP28 in Dubai, countries agreed on a set of 11 targets that will guide countries in their efforts to protect their people and ecosystems from the impacts of climate change. One of these 11 targets is health.

Experts were then identified to come up with a list of indicators that could be used to track progress on these targets.

In Bonn, these experts presented a draft of possible indicators across the 11 targets, including indicators for tracking progress on health. This list of 490 indicators can be found here (see tab 9(c) for health indicators).

Importantly, two mental health indicators have been proposed:

- One indicator on suicides attributable to climate sensitive extreme-events

- One indicator on mental health services emergency admissions attributable to climate sensitive extreme-events

The choice of these indicators is backed by extensive evidence highlighting the relationship between certain climate stressors and these mental health outcomes. For example, in the context of extreme heat, we tend to see an increase in the incidence of suicidal behavior and completed suicides. In Australia, it was estimated that approximately 0.5% of all suicides between 2000 and 2019 (an estimated 264 deaths by suicide) could be attributable to climate change-induced heat anomalies. Across the United States and Mexico, unmitigated climate change has been projected to result in a combined 9,000-40,000 additional suicides by 2050. Certain groups appear to be particularly at risk, for example emergency hospital admissions for suicidal thoughts and behaviors among young people were found to increase by 1.3% for every 1°C rise in daily mean temperature in Sydney. The reason behind these associations is likely the result of multiple interacting factors, from disrupted sleep patterns to difficulty in accessing usual coping mechanisms such as outdoor physical activity and socialising when it’s too warm outside.

Beyond heat-waves, various other climate sensitive extreme events such as droughts and floods have been shown to contribute to increased suicidal ideation and non-fatal attempts.

What happened in Bonn this year?

At SB62 in Bonn, following extensive negotiations across the two weeks, countries provided a mandate to experts to further reduce the list of indicators to no more than 100 indicators. The final agreed structure would be made up of globally-relevant headline indicators, complemented by a more context-specific set of sub-indicators which countries would be able to pick and choose from. Additionally, countries agreed to include indicators for adaptation finances (also known as “means of implementation” (MoI)) within the GGA.

For a comprehensive analysis of the draft conclusion document from the GGA negotiations, see here.

Experts are expected to submit their final technical report in August 2025.

Why we need to ensure mental health is tracked as part of the GGA going forward

Mental health has historically been absent from adaptation discussions. For example:

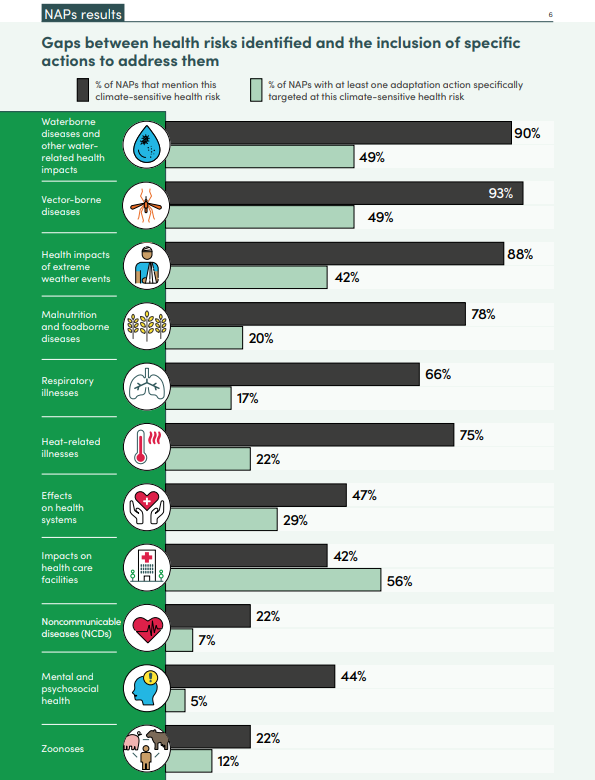

- A recent 2025 World Health Organisation review of health in national adaptation plans found that only 5% of NAPs and 22% of Health-NAPs (HNAPs) included specific actions to address mental health and psychosocial needs, making mental health one of the health outcomes with the least actionable recommendations in the context of adaptation policies.

- Another recent review on children’s health in NAPs found that of the 160 countries it examined, none included considerations on children’s mental health.

Graph showing the gap between NAPs identifying mental health as a climate sensitive health risks and those including specific actions to address them (WHO, 2025)

Graph showing the gap between NAPs identifying mental health as a climate sensitive health risks and those including specific actions to address them (WHO, 2025)

One of the likely reasons for this lack of attention to mental health in adaptation action stems from the lack of tracking of the mental health impacts of climate change. For example, according to the WHO 2021 Health and Climate Change global surveys, only 21% (14 out of 66 countries) of countries have climate-informed health surveillance systems in place for mental and psychosocial health.

This must change. The GGA represents a historical opportunity to ensure the mental health of people and communities around the world is protected from the impacts of climate change. There can’t be resilient systems without resilient people. We are calling on countries to ensure mental health remains included in the GGA to enhance adaptive capacity, strengthen resilience, and reduce vulnerability to climate change for all.