Making the case for ending institutionalisation in mental healthcare

Hear from Ali Hasnain, our Policy & Advocacy Advisor, about our work on the deintitutionalisation of mental healthcare.

10th July 2025

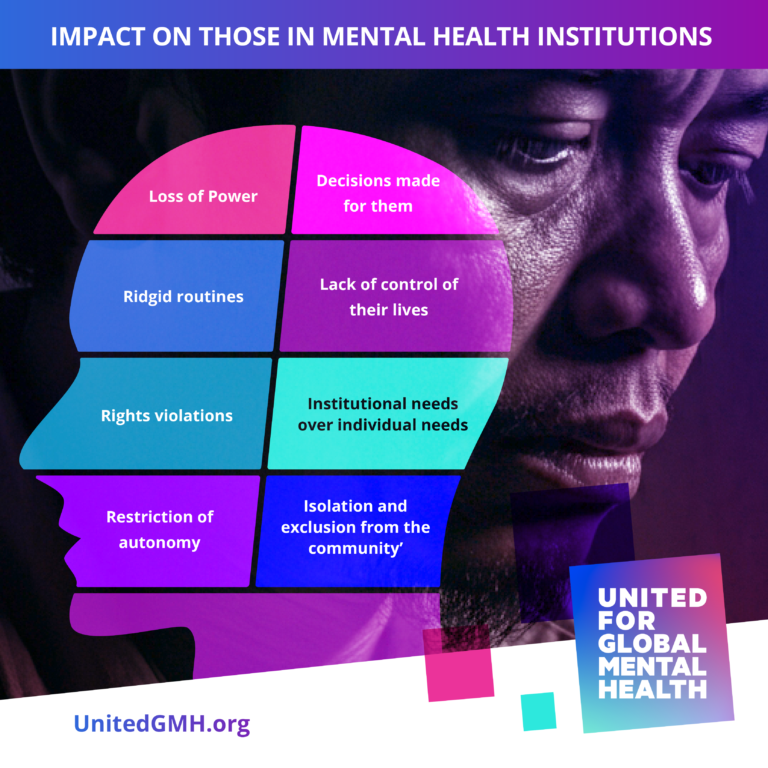

The world holds more people in institutions for their mental health every year than it does individuals in prison for committing crimes. They can spend years in institutions, unable to speak up for themselves or have anyone speak up for them. They are out of sight and out of mind, as captured in our report of the same name, which not only identifies all forms of institutions but talks about how many people are in them and the many different and at times shocking reasons they are there.

Our team at United for Global Mental Health aims to bring an end to such institutionalisation, by amplifying the voices of those who have spent time in institutions, have been affected by institutions or are working tirelessly for a transition from institutions to system reforms allowing recovery oriented care in communities. Through a series of reports, we hope to capture the experiences of these people, their recommendations for reform and showing pathways to policy makers to achieve these reforms. This includes areas such as legislation, policy, programs and financing, as well as cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder collaborations to achieve change.

We hope to use forums such as the World Health Assembly and the UN General Assembly to position the ending of institutionalisation as a global priority. Achieving this will only be possible if we serve as conveners for people most impacted by institutions to directly advocate with their governments at these global gatherings. Friendly governments, including Portugal, Mexico, Brazil and Guyana are already championing the issue at the global level to ensure world leaders commit to ending institutionalisation at the global level and we will support them to achieve and then see implementation of these commitments nationally.

Many of our partners have been trailblazers already in this space and we hope to amplify their great work. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has already developed guidance documents on mental health legislation and policy that talk extensively about deinstitutionalisation, with a comprehensive guideline report to follow. The Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR) partnered with the WHO on the legislation guidance and also ensured that deinstitutionalisation was the subject of conversation at the World Health Assembly in 2025 by hosting a high level event on the subject. Human Rights Watch has done a series of reports and case studies on deinstitutionalisation, including a groundbreaking report on the abhorrent practice of shackling. These are just some of the actors pushing for change and we will partner with them to ensure their messages reach those able to affect change.

Why deinstitutionalisation now?

2025 brought with it a unique opportunity to cast light on some of the most neglected issues in mental health. The UN General Assembly in September will host a first ever high level meeting dedicated to mental health, where discussions on subjects like mental health system reforms and financing will take center stage, translating into commitments. These discussions will have institutions at the heart, as they are currently seen as the main form of care for people with mental health conditions, and 66% of national mental health budgets globally are spent on them.

Conversations around reorienting health systems towards primary health care and community based care are also increasingly taking place at global forums, and we are seeing wide ranging reforms to this effect in many countries, including Brazil, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Lebanon and others. The WHO recommends transitioning care from tertiary institutions to communities, whilst strengthening the health system as a whole, so this is an opportune time to ride the waves of existing reforms and bring a gradual end to institutionalisation.

Most importantly, there are still people in institutions, locked away, deprived of basic human rights, subjected to all forms of unacceptable and illegal acts, forcibly admitted and treated. There are still families suffering on account of needing to send their loved ones to institutions given they have nowhere else to go and no other choice. There are members of the mental health workforce that are working in dire conditions for ungodly hours without adequate remuneration, often questioning the very premise of the supposed care they are meant to provide. And then there are those that have left institutions but are unable to find employment or even acceptance in their communities. We are already too late for many of them, so it is no longer possible to wait to advocate for their rights.

What do we really hope to achieve from our deinstitutionalisation work – short to medium to long term?

In the short term, we are developing advocacy tools to complement the WHO’s technical guidance documents, which can be put to use by national advocates at country level. We also hope to achieve commitments to deinstitutionalise mental health care at the UN High Level Meeting on NCDs and Mental Health at the UN General Assembly in September that can be leveraged by these advocates nationally.

In the medium term, we hope to see national advocacy campaigns that lead to legislative and policy reforms across multiple countries and for these reforms to spread across the globe through coordinated action facilitated by continued discussions at global forums and coordinated advocacy convened by the Global Mental Health Action Network.

In the longer term, with laws and policies in place, we hope to see countries slowly redirect resources and increase financing to reform their mental health care systems to rely on community based care, with support from primary, secondary and where appropriate short term tertiary care, phasing institutions out entirely.

How does deinstitutionalisation tie in with United for Global Mental Health’s other work?

Ending institutions is the cornerstone of our work on human rights, as they are the place where most human rights abuses are reported. There are far too many children in institutions currently, some of whom spend their entire lives in them, so our work on children and youth mental health cannot ignore them. People in institutions are impacted heavily by the impacts of climate change and the spread of diseases such as HIV and TB, necessitating their integration into preparedness and response to such threats. Our work on generating more financing for global mental health cannot ignore that at present 66% of national mental health budgets worldwide go to institutions, which is not an efficient use of resources.

Most importantly, our vision for a world where everyone everywhere has access to good mental health cannot be accomplished whilst institutions still remain the primary source of mental health care. There cannot be more people involuntarily confined in institutions than there are in prisons. Mental health care should not feel like a sentence. Let’s change that.