World Suicide Prevention Month 2025: What My Faith Never Told Me About Depression

Written by Carol Labor, DrPH, Senior Mental Health Adviser and Chief Mental Health and Wellbeing Officer, NPHA, Sierra Leone

There was a night, in fact, many nights that I did not want to wake up.

On the surface, my life appears unchanged. I continue to fulfill my responsibilities, maintain my social obligations, and uphold my usual routines. To those around me, everything seems normal. Internally, however, I experience a persistent profound sense of detachment. At times, I feel as though I am observing my life rather than living it. It is not sadness in the conventional sense but rather an emotional void. This heaviness, persistent and wordless, resisted all attempts to explain or resolve it.

In the cultural environment that I was born into, mental health challenges are not openly discussed and psychological distress is often dismissed or spiritualized. When individuals express emotional pain, they are frequently met with comments such as “nah fu beah (Be Patient)” , “u yone betteh (Yours are better).” or “Nah fuh pray (You must pray).”

These responses are often intended to comfort, but they instead repeatedly reinforce the belief that experiencing mental health challenges reflects a lack of mental and emotional strength; a lack of resilience. Rather than being seen as a health issue, depression and suicidal ideation are treated as moral flaws.

For a long time, I accepted this interpretation. I kept going, suppressing what I felt, until one evening, the first of many, the thought emerged quietly and persistently. I questioned whether continuing to live held any value. I do not remember precisely what interrupted the thought. It may have been the sound of a familiar voice or the recollection of a past conversation. Somehow, I chose to remain. I choose to remain despite it all. This conscious choice, small and almost imperceptible, is a turning point.

Following this experience, I began the process of seeking help. I pursued therapy, began a course of medication, and allowed myself time to recover over and over again, accepting that I live with suicidal ideation. Alongside professional support, I confronted long-standing beliefs that my faith required me to suppress pain.

I vividly recall a conversation with a religious leader during a mental health crisis (I called him) who dismissed me. I reconsidered what it meant to suffer and to survive. Eventually, I came to understand that genuine faith does not require concealment which hinders my authenticity as a global mental health expert.

Silence in the Name of Faith: A Wider Crisis

Unfortunately, my personal story reflects a much broader public health challenge. As mentioned by the World Health Organisation, an estimated 727,000 individuals die by suicide every year. In Sierra Leone itself, a country I remain deeply connected to, suicide remains a major and under-acknowledged concern with the suicide mortality rate was estimated at 6.1 deaths per 100,000 people in 2021.

Despite this reality, mental health services in Sierra Leone remain severely limited. The country, with a population of over eight million, has only one functioning psychiatric hospital. There are few trained professionals and limited access to community-based care. In addition, widespread stigma discourages individuals from seeking support. The result is a dangerous silence.

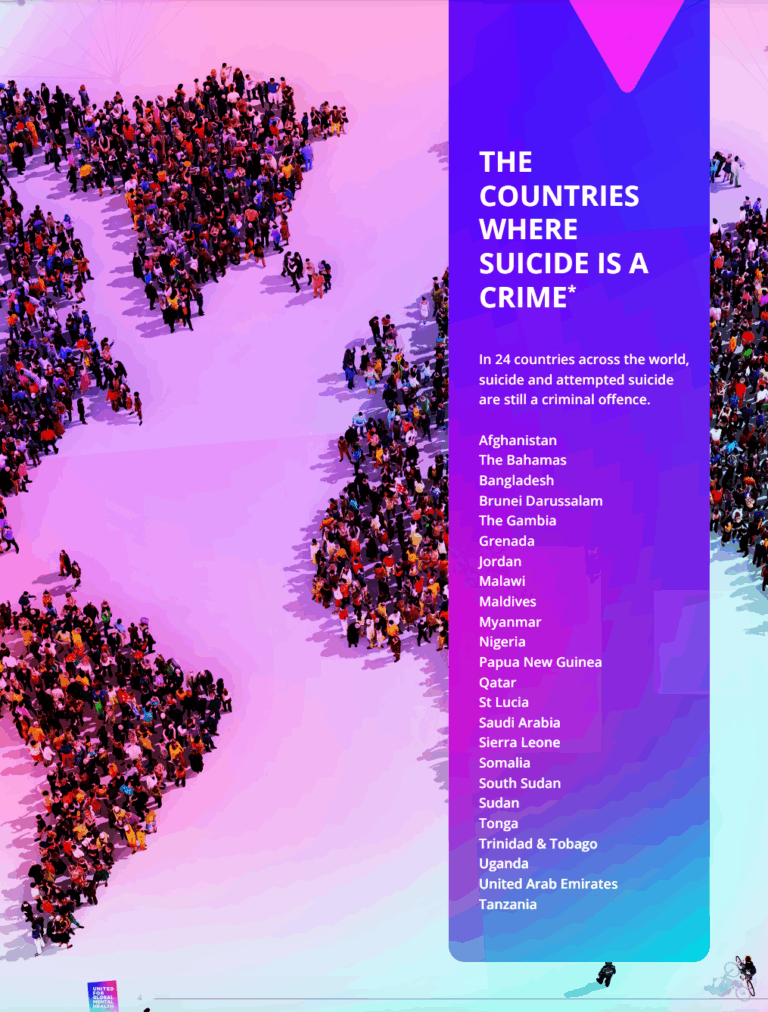

When we look closer at the suicide phenomenon, we realise that this silence is not only social or institutional but also deeply legal and historical. As mentioned in the recently published report by United for Global Mental Health, suicide and suicide attempts were criminalised in many countries until the nineteenth century. Across diverse legal and cultural settings, the idea that criminalisation deters suicide continues to influence public attitudes and policy, even though this belief has been thoroughly debunked by global research.

Suicide Prevention Month 2025: From Silence to Solutions

What is required, then, is a multidimensional response. We need to shift the narrative—from silence to solutions. We need mental health policies that are funded and enforced. We need religious and cultural leaders who stop preaching shame and start practicing care. We need media that tells the truth that depression is real, that suicide is preventable and not a crime, and that recovery is possible.

Religious communities, particularly in contexts such as Sierra Leone, must assume a leadership role in advocating for the decriminalisation of suicide. By challenging archaic laws that treat suicide as a crime, faith leaders can help pave the way for compassionate, health-centred approaches that prioritise care, prevention, and the dignity of every individual.

This World Suicide Prevention Month, I offer a message that I once needed to hear. Experiencing pain is not a personal defect. Asking for help is not a betrayal of strength or faith. Choosing to live, even through difficulty, is an act of profound bravery. Faith, if it is to mean anything in the face of that, must begin with compassion.